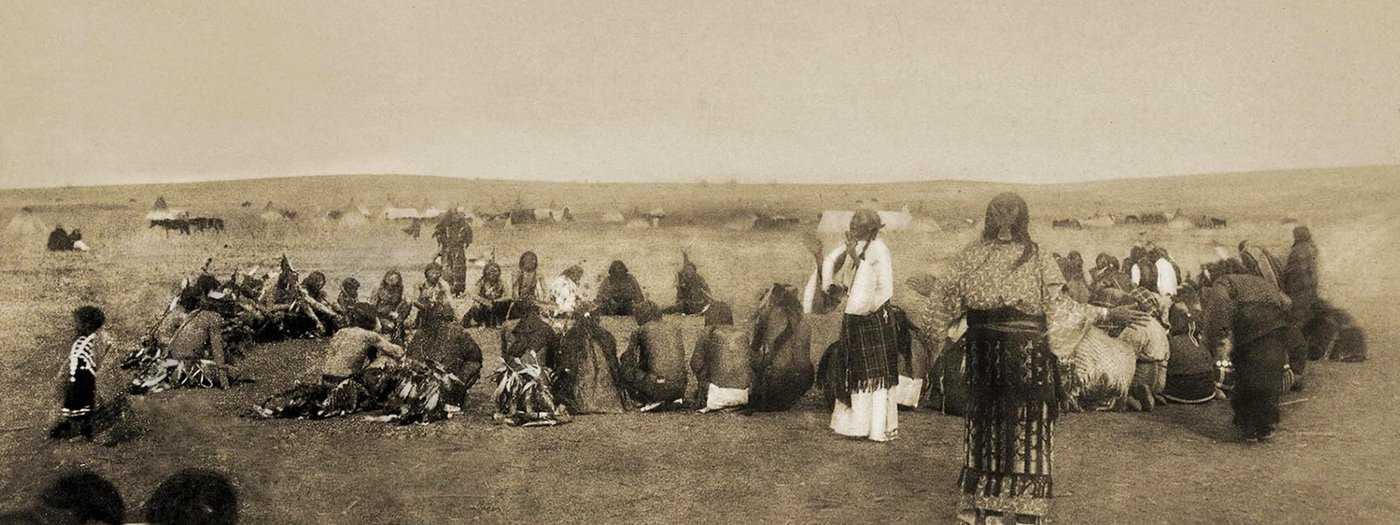

Almost thirty years after the hanging of the Dakota, in December 1890, the US Cavalry opened fire on a camp of nearly three hundred Lakota ghost dancers near Wounded Knee Creek on the Pine Ridge Reservation of South Dakota. The fully armed US Cavalry came to one of these camps with a Hotchkiss gun, a cannon with a rotating barrel, and the intention of disarming the Lakota. One Lakota man refused to give up his rifle, and according to some witnesses, the rifle went off when he was grabbed by soldiers. The US Cavalry opened fire. At least 150 Lakota were killed and fifty wounded, including women and children. Because of a blizzard, it would be three days before the dead were buried. Twenty US soldiers were later awarded the Medal of Honor.

Visiting Wounded Knee has become a kind of pilgrimage for Indigenous people. At some point, we all think about standing in those fields. We think about the ghosts that dance around us. Even if they aren’t our ghosts, we know that they are relatives and that their losses are also ours. I went to Wounded Knee with my husband and middle son, Max. In the Badlands of South Dakota, undulating grasslands drop off abruptly into distinctive rock formations. Sharp canyons and tall spires in red and gray layers dominate the landscape. At the Wounded Knee memorial, visitors tie tobacco ties—small scraps of cloth wrapped around pinches of tobacco—to the fencing. I added my own ties to those fluttering prayers, creating a visible presence of people who had disappeared.

When we arrived at the memorial, storm clouds were gathering. A friend’s cousin, Pte San Win, whose ancestors had been massacred at Wounded Knee, met with us. By the time she arrived, the wind made it impossible to talk, and we fled to our cars to wait it out. The wind eventually died down, and the sky cleared. When Pte San Win and I stood on top of a low rise, the world felt scrubbed clean. I looked down at the grasslands and thought about her relatives disappearing beneath the Hotchkiss gun, disappearing beneath the blizzard, disappearing into a mass grave.

(from Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting Our Past and Reimagining Our Future)

I went to Wounded Knee as part of a road trip west to Vancouver Island. We started at the pow wow at Nipissing First Nation outside of North Bay Ontario. It got rained out, we call it the rain pow wow because it invariably rains that weekend, and we left after the first day. I wasn’t going to, but when I went into the tent after dinner there were puddles inside so we packed up and drove off into the night. Rain would dog this part of the vacation. We hung the tent and sleeping bags up inside our Sault Ste Marie motel room, one of many Super 8s that we stayed at over the course of our three week trip. At one point the rain was so bad that I could barely see and took the first exit off the highway, winding up in in a town called Blue Earth Minnesota. I don’t remember if we saw the statue of the Jolly Green Giant.

We stopped for lunch in Rosebud, a reservation near Pine Ridge where the Wounded Knee Memorial is, and I snapped a photo of what I thought was a neat cloud formation, much like the one above, except we were directly beneath that circular mass. I had heard tornado warnings on the radio but this was just a round cloud right? I sent it to the friend whose cousin would be meeting me and she responded with a terse “get out of there.”

So we did.

When we arrived at Wounded Knee it was cloudy but ok. People came out of nowhere to sell us earrings and dreamcatchers. I told one young boy that dreamcatchers were an Anishinaabe thing and he asked me if we made them with tipis like his mom does. It still hangs on my rearview mirror alongside one that I picked up in the Bahamas. By the time Pte San Win arrived the wind had picked up as the rains that had tracked us from Nipissing descended.

Afterwards Pte San Win, whose name contains the story of White Buffalo Calf woman, told me that this is common. These storms that scrub the landscape when people come to Wounded Knee. It is sacred space, thin space where the past and the present don’t feel so far apart and that amount of energy needs resetting or cleansing or something. I don’t know. Maybe it’s a kind of ceremony for those of us who come here seeking belonging and connection.

It was at the sunrise ceremony that started this road trip that an elder named me daanis. I don’t mean that he named me in a conventional naming ceremony. It was after the sunrise ceremony when we all greet each other and when he greeted me he said daanis, which only means daughter but it felt like a name and when I created my twitter account a few months later that became my handle. While we sat in the car Pte San Win gave me a pair of earrings, she said that they represented the morning star and she wanted me to have them. It would be several years before my father gave me an Ojibwe name. Wabanan Anangonkwe: Morningstar woman.

Names are profound, every parent and pet owner knows this. We agonize over getting it right, about the literal meaning and the social context (that is: does it remind me too much of an ex I’d rather forget). We think about what nicknames could emerge from it. Is it unique enough? Is it too unique? Am I condemning my child to a lifetime of correcting people’s spellings. And this trip, this pilgrimage to Wounded Knee which so many Indigenous people undertake, brought me two names that connect me to my community in different ways.

Daughters have specific family responsibilities, and in the Ojibwe creation story, Morningstar Woman is the firekeeper’s daughter which is an interesting connection between the two names. She becomes the wife of the first man, Anishinaabe, and the mother of four sons. I have three, but I also have a grandson so that’s four. I could keep finding meaning in that story. The sons were named for the four directions. I have one who loves the north, one who lives out east, one who is connected to our family in the west. Which leaves the south for my grandson which is nice for him because it’s warm. But sometimes we just look for meaning because we want to find it and not because it’s actually there.

The Ghost Dancers were also seeking meaning. The people had experienced so much loss, it’s impossible to imagine how devastated they were. Centuries of genocide and sickness. Even if General Amherst wasn’t successful with his smallpox blankets, he was willing to try and as a whole settlers were willing to exploit something they didn’t fully understand. There is no wilderness, Patrick Wolfe writes, only depopulated spaces.

So the people danced. They danced to bring visions and bring about a vision: restore the land to it’s former existence and rid themselves of these white men who brought only hardship and grief. They danced and the government felt this to be a threat. An existential threat perhaps, people who weren’t properly grateful for everything that the Great White Father was doing for them. People who weren’t properly submissive or accepting or willing to assimilate and vanish so that settlers could just take the land and wouldn’t have to steal it. People who wouldn’t just die and needed to be killed.

The people still dance. We danced even when it was illegal and now we dance at pow wows and protests. In 2012 when the Idle No More Movement started in Canada there were teach ins and gatherings but what I remember the most was the round dances. Taking over public spaces from shopping malls to busy intersections we danced and like birds getting ready to migrate, every time we danced we gathered in more people. We dance because it connects us to each other in all directions. It connects us backwards in history with those we can no longer see but who see us. It connects us with those yet unborn, watching from spirit world and waiting to choose their parents.

It connects us to those who aren’t us, because anyone can join in a round dance. We hold hands and dance in an ever widening circle until we are all connected. We are all connected. All of us.