What Strange Paradise

Peter Pan, migrants, and the losses that create us. Here there be spoilers.

The scene is familiar. A small child lies on a beach with his head towards the ocean and feet on dry sand. The image of Alan Kurdi, a three year old Kurdish Syrian boy has become part of the global psyche and in his book, What Strange Paradise, Omar El Akkad begins with the same image. But in this version Amir is a few years older. And he gets up.

If you haven’t read this book I would encourage you to bookmark this essay and go read the book first because there will be spoilers. Not at first, and I’ll warn you again when I get to them. But just to be safe, bookmark this and come back after you’ve read the book. You won’t regret it. The book sits nicely in your hand, has a lovely cover, and the moment you finish it you’ll want to read it again it’s that good. Then you’ll want to put it into the hands of your liberal friends, the ones who voted for Biden and not Trump. The ones who marched on Washington with pink hats. The ones who opposed the Muslim ban and cried about children in cages. Because ICE-loving patriots are not who this book about migrants is for.

It’s for us.

The book opens with a wrecked migrant ship and then the story unfolds telling the before and after of Amir’s life on either side of this shipwreck. The family begins in Syria and makes their way to Egypt. Amir gets onto the boat by accident, following his step-father, who Amir calls Quiet Uncle because he is a quiet, passive man. Quiet Uncle has purchased passage across the Mediterranean Sea for himself and one night when he goes out Amir follows him to the dock and then onto the boat. When he is discovered, rather than allow him to become property of the smugglers, Quiet Uncle pays for his passage which allows Amir to stay topside on the boat while his uncle is forced below decks.

Below decks is where the mostly African migrants are. The smuggler’s apprentice Mohamed insists this has nothing to do with race and is only because they cannot afford the higher cost to ride above but the migrant he is speaking to doesn’t buy it. Keep telling yourself that, he says. This is uncomfortably like the Middle Passage, another perilous journey in which Black bodies were crammed into dark spaces by those who profited from their misery. Black bodies who were both needed for labor and resented, seen as bodies and not people, bodies for labor that are interchangeable and disposable. These are not captives bound for slave auction, but those racist hierarchies remain inscribed on their skin and in this journey as in the one before, people who were Eritrean or Somali or Igbo or Yoruba become Black.

Throughout the story we see how people disconnect themselves from migrants. Amir’s aunt, living in Damascus and the first place of refuge the family seeks, cannot believe that the destruction of Homs is as bad as all that. The media has overdone it she insists to the woman who just lived through it. In the aftermath of the shipwreck that spilled bodies of migrants onto it’s beach, a hotel apologizes to tourists for the inconvenience. This contrast is shown again and again, the need to believe it wasn’t that bad, the euphemisms that sanitize our speech.

This summer the remains of children were found at Indian boarding schools in Canada and the US, and still many want to believe it wasn’t that bad. Health care systems are overwhelmed with people sick with Covid and many want to believe it isn’t that bad. Liberals blame Trump for all sorts of injustice and remain honestly surprised by his ascendancy to power because they believe that the beliefs which create the inequities of racism and capitalism aren’t that bad. Obama ushered in a “post-racial era” and Trump is some kind of aberration and not just Tuesday. Liberal pundits insist that this is not who we are every time they are faced with America being who it is.

In his flight from the workers who come to the beach, Amir is befriended by a young girl named Vänna. His own mother is back in Alexandria, Egypt and El Akkad gives this little boy mothers. On the ship there is a pregnant woman named Umm who cares for him. On land it is Vänna who is dissatisfied with life on the island and has a troubled relationship with her own mother. Together they seek help from a different mother, the former principal of Vänna’s school who now runs the refugee processing camp. Rather than admit Amir to the questionable supports of the migrant camp, she gives them information about a ferryman who will take Amir off the island to a large city where a migrant community will take him in. These women take care of Amir and one after another they provide moments of safety in his unstable world. Unlike his own mother who was left behind, who was unable to protect him, Vänna who is white and western will leave everything behind and keep him safe. She will journey with Amir to his new life on a proper boat.

El Akkad gives Amir fathers as well, but they are less kindly. Less helpful. His own father is gone, probably dead. Quiet Uncle is ineffectual and passive, willing to abandon the family he took on as a responsibility after the death of his brother and whose actions put Amir in danger. The smuggler’s apprentice teaches the migrants about the west and the futility of hope. And the general, a man embittered and disabled by one of the interminable wars that the west instigates in the Middle East, searches relentlessly for one small survivor.

The setting itself is unmoored and unstable. The Before has a multitude of settings: Homs, Damascus, Cairo, Alexandria, the Mediterranean Sea. After is familiar, an unnamed island that is probably Greek. There are flora and fauna that don’t exist in the world, a reptile hinted at. The story is anchored in relationship because that is what migrants have. They don’t have place, unmoored from home and unwelcome here they form connection with each other against the unknown.

It is a Peter Pan story with a strange land populated with pirates, a lost boy, and the young girl who mothers him. A desperate journey towards the second star on the right and then straight on ‘til morning. For a brief moment we believe in the magic of happy endings. But there are hints of darkness throughout the book, early on Vänna finds severed wings and she imagines a bird was eaten by something reptilian that hides in the bushes. Tinkerbell did not survive. Just as in Neverland, there is a crocodile in this strange paradise.

Now we come to the spoilers.

There is no happy ending.

The book, a series of chapters titled Before and After ends with Now and it returns to the scene on the beach. But this time instead of Amir waking up and fleeing into the woods, a masked worker lifts the distinctive locket from his neck. Amir did not survive. Did not meet Vänna. Did not get costumed in Cleveland Indians t-shirt. Did not eat cookies. Did not sleep in the lighthouse. Did not make it to the ferryman. Did not grow up and have a happy ending.

There are theories of course, about what the After chapters mean in this book, if they are a dream or an alternate reality and some, like Amir’s aunt, refuse to accept that it could be that bad and find a way to believe he survived. I think they are aimed directly at mostly white liberals. This is the story we want. We want little Alan Kurdi to get up off the beach and survive, become a Good Migrant who overcomes adversity and shows us how important migrants are to our economy and western world. We want to save the starfish while ignoring how we enable and support the system that flung them onto the beach in the first place.

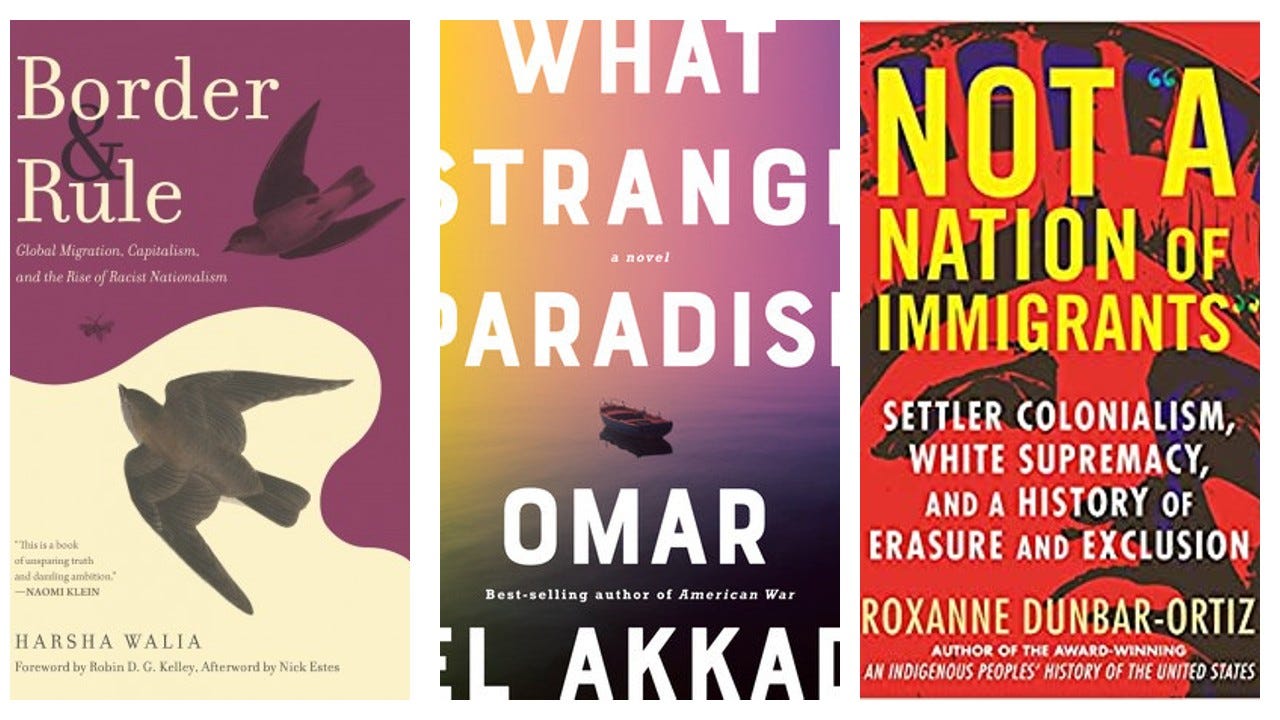

I’ve written before about Harsha Walia’s book, Border and Rule, and I want to return to it now because she outlines the ways that bordering regimes act to move the responsibility for migrants further away from the physical borders and then tie that demand to aid projects, forcing countries impoverished by western imperialism to become it’s border guards. Germany, the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, etc all outsourcing violence and harm to places where we can’t see it, places that we can then go on to describe as corrupt and violent while we sun ourselves on beaches cleared of bodies that shouldn’t have been there in the first place. Management apologizes for the inconvenience.

In the introduction she writes that individual migrants are sympathetic. They are models of success and assimilation. Amir sheds his sea-soaked clothes for something that will help him blend in: a tourist child’s tshirt bearing the logo of the Cleveland Indians (before the name and logo change). What could be more American. The first name he chooses for himself is David, the name of an erstwhile and ineffective aid worker mentioned periodically while the family is in Alexandria. It is only as he begins to trust Vänna that he shares his true name. Amir is sympathetic, relying on the charity of a white girl who finds purpose in helping him.

Collectively however, Walia continues, migrants are a threat and the language of uncontrollable water is invoked against them. Large numbers of migrants are a flood. Borders are swamped. We turn away from large numbers of them and focus on these individual stories. More troubling, we focus on children. We weep about children in cages but not their parents. Toddlers don’t come to the border alone. They have parents who are criminalized by a system that may want their labor but doesn’t want them. In her new book Not “A Nation of Immigrants,” Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz demonstrates how the US has consistently wanted the labor of those who come from elsewhere, but it doesn’t want them. Racial hierarchies and beliefs about others keep them in place while their labor is extracted and them criminalizes them when it is no longer needed.

By offering us this picture of Amir’s rescue and then taking it away El Akkad takes aim at this tendency that Walia writes about, this myth that Dunbar-Ortiz unravels. He gives us the individual migrant child and then takes it away, returning Amir to his community and away from our charity.

No happy ending for you.