Years ago while asking the Google machines about my relatives Moses and Noah Wesley I came across the book Treaty No 9 by John S. Long. They are mentioned in it and there is a chapter on Lac Seul. Lac Seul is covered under Treaty 3, but it was an early stop for the commissioners who were travelling further north. Patricia Ningewance, a language teacher and knowledge holder from Lac Seul, reviewed this chapter and her response is quoted:

“I cried reading about the mentions of the Mide ceremonies and how Lac Seul used to be well-known for its Mide activities. Now the island where Mide ceremonies used to be held is officially called ‘Devil’s Island.’ Its name in Ojibwe was always Manidoo Minising, which means God Island or Spirit Island. It is so difficult trying to bring these ceremonies back to the people, but we will.”

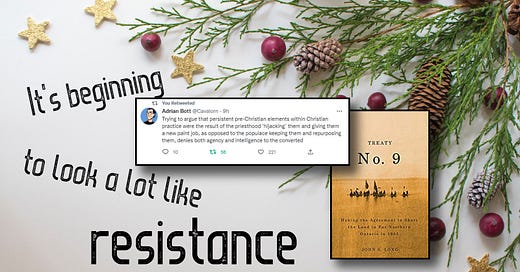

Treaty No. 9: Making the Agreement to Share the Land in Far Northern Ontario in 1905 is told in three parts: the historic context, the historic documents, and an analysis of the process. The documents are fascinating, they are the diaries of the commissioners themselves (one of whom was Duncan Campbell Scott) and reveal their own thoughts about the Indians, what they had been tasked to do and the limited information they gave to the people in order to do it. While at Lac Seul, Scott advised the Indians that they would have to give up their “Dog dances and other ceremonies contrary to the Treaty laws.” A medicine man responded (cunningly, noted MacMartin’s diary entry) that if the commissioner would consult Powassan and if Powassan said that he agreed, they would give up the “barbarous practice.” Scott was, the diary notes, suddenly taken ill that evening. [smirking emoji]

There is a lot that is interesting about this book, like the concern of the commissioners that communities closer to Lac Seul and Treaty 3 would want the same deal that the earlier signers had been given, because what was on offer with Treaty 9 was more limited. However, the interesting story I wanted to share had to do with a church. While they were in Moose Factory the Treaty ceremony was held in a hall where church services also took place. Hymns were sung in Cree and while the commissioners were there the hall was filled every night by “interested Indians” who “took an intelligent part” in the services. That stuck in my mind because of something else I had heard about Indians in churches during the turn of the century.

It was cover.

Not always, but often participation in church services provided cover to other organizing that was taking place elsewhere in the building. Nobody would think twice about a prayer circle going on while the community was singing and listening to the preacher. For decades in Canada and the US it was illegal for Black and Indigenous peoples to gather in large groups or participate in ceremonies. Although in Canada the law technically applied to the potlatch and other ceremonial gatherings, throughout the 1920s it was broadly applied so that Indian agents could charge or convict Indigenous people for almost any kind of gathering. So, by giving the appearance of participation, people whose ability to gather together was controlled and monitored, could gather together.

This came to mind because of a tweet that I saw earlier today. Twitter user @Cavalorn tweeted out that “trying to argue that persistent pre-Christian elements within Christian practice were the result of the priesthood ‘hijacking’ them and giving them a new paint job, as opposed to the populace keeping them and repurposing them, denies both agency and intelligence to the converted.” He further notes that the Venerable Bede, an 8th century monk, wrote that it was the English “people” who kept on referring to the new festival by the “time honoured” name of the old one. It wasn’t the Christian Priesthood who changed the name from Pascha to Easter. It was, according to Bede, the people themselves who used the name Eostre, a goddess in whose honor they had feasts during the month of April.

People keep their old habits. And sometimes they do the expected thing because it allows them to maintain contact with the forbidden thing. Like the Green Men in church chapels. The Green Man is an ancient symbol of rebirth found in multiple ancient cultures and images of him have been found from Lebanon to England. While we were in Edinburgh we went to Rosslyn Chapel (yes, because I’d watched that Dan Brown movie) and saw the Green Man carvings throughout the chapel amongst the others.

So thinking about these things, about the populace keeping their old ways and repurposing them in the context of Indigenous religions or practices being banned made me think differently about how and why these old ways were repurposed. And whether that need still exists.

It’s complicated. Things are always complicated. No doubt there were true believers singing hymns and listening to the sermons. Missionaries who come to traumatized communities have the advantage after all. The impacts of colonization from indirect harms like epidemics and climate change to direct harms like extraction industries and forced migration leave communities devastated. And their belief system may not be equipped to deal with the mass death and trauma they have just experienced. Think about a trauma you experienced, think about how fast you blamed yourself and tried to figure out what you had done to cause it. That’s not just victim-blaming, that’s an attempt to feel safe and confident that you can prevent it from happening again. Communities do the same thing. Spiritual communities want to know how they offended the gods or the spirits. Did their ceremonies fail them? Most belief systems have a kind of quid pro quo thing going on, you take care of the spirits and the spirits will take care of you.

When missionaries come into these traumatized communities they have the answer to that question. It wasn’t that you didn’t take care of the spirits, it’s that you were taking care of the wrong one. That’s why this happened to you. It may not be said that plainly, but that’s what gets communicated and people whose elders may no longer be alive or able to offer a different interpretation, are vulnerable. So no doubt many of those who sang the hymns and participated (intelligently lol) in the services were now true believers.

But they brought something with them. The priests did not need to repurpose the cedar boughs we bring inside or the lights we put up to make them about Jesus so that we’d join their church. We brought that stuff with us into Christmas which is close to solstice. And if solstice is going to be illegal then perhaps we can do it a few days later under a different name.

But does that need still exist?

Do we still need to participate and perform as a kind of cover for doing the things we are otherwise not able to do. A lot of Indigenous people are rejecting Christmas and celebrating solstice instead. With our religious practices not only legal but protected under human rights legislation it is less troublesome. We can say that broadly speaking it isn’t necessary, but families and communities have their own social pressures. It may not be illegal to have a sweatlodge, but that doesn’t stop Indigenous Christians from tearing them down and declaring them pagan. I made a ribbon skirt for a young woman to wear at her university graduation who would face judgemental looks if she were to wear it in her home community.

It’s difficult, as Ningewance says, to bring our ceremonies back. Sometimes they come back with Christian trappings, like the ribbon skirt which has its own complicated history, that need to be examined. People keep their old habits after all. But they are coming back, and sometimes what looks like Christmas might actually be resistance.