Toward What Justice?

The moral arc of the universe bends, but towards what justice? Justice for who?

The Tuesday essay is coming to you on Wednesday. As my husband noted, right out of the gate I’m letting you down but I spent yesterday writing an op ed that won’t be published #probably and then I updated my bio and wrote a synopsis for a workshop I agreed to do later in July that was due a couple of days ago. It actually sounds like something I’d like to go to so that’s pretty good. Then I started answering questions for the author’s questionaire my publisher sent me months ago and then it wasn’t Tuesday anymore.

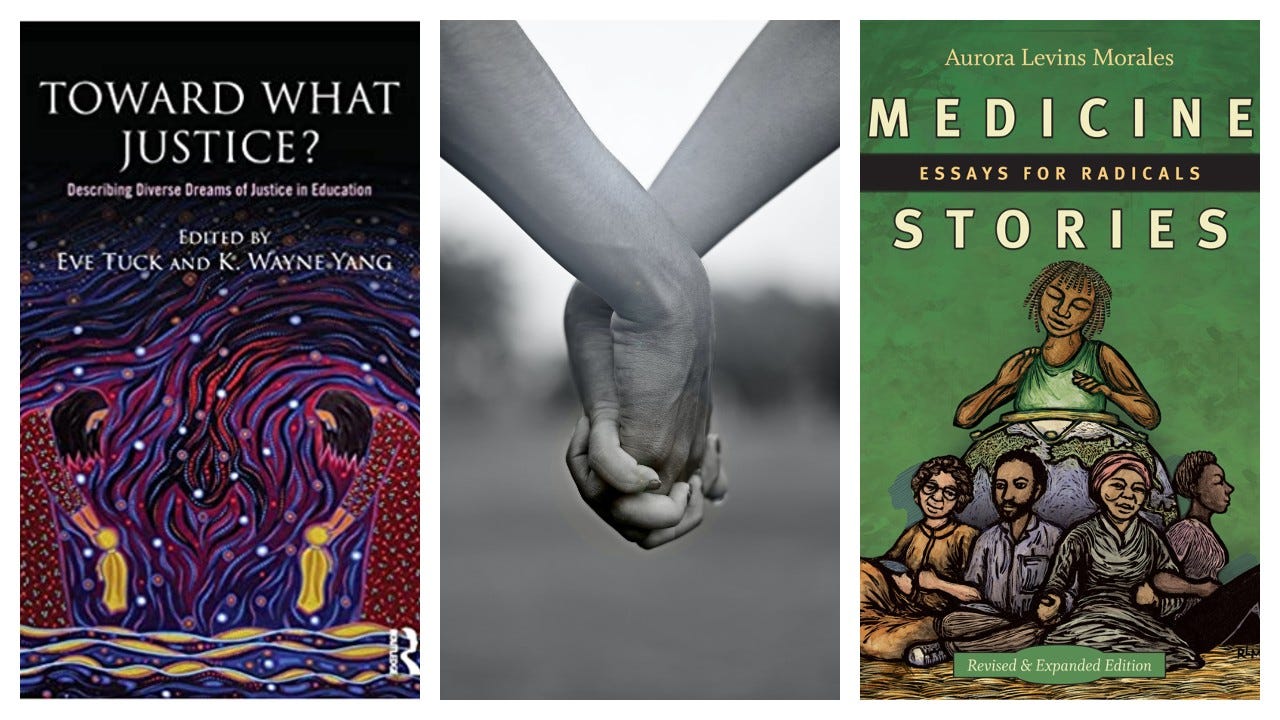

I started a new book today, Toward What Justice which is a collection of essays edited by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang subtitled “describing diverse dreams of justice in education.” It’s one of the books I’ve been meaning to get to but haven’t and since I couldn’t remember which book I intended to read next it seemed like as good a choice as any. I’d been taking pictures yesterday about book covers I like and this is one of the ones I took a photo of. The cover, by Christi Belcourt, is stunning as her work always is.

The book takes it title of course from a speech by Martin Luther King Jr in which he says that he believes the moral arc of the universe bends towards justice and then troubles that statement. Whose justice? Which justice? Because there is no consensus on what justice looks like or how we will get there. Social justice is a broad umbrella that contains groups who aren’t always working in each others’ best interests, if not actively undermining each other they often forget about the needs of other groups and make vague promises to come back for the ones who are being left behind or are simply unconsidered. The problem with that is that we never arrive at that place of justice, and so there is no moment when it becomes possible to go back for those we have sacrificed on our way to justice.

Tuck and Yang talk about incommensurability, that tension that exists between groups who can work together for a time while anticipating that our paths towards enacting liberation will diverge. Kelly Hayes (Truthout.org, Movement Memos) often talks about making strategic alliances with those whom we have enough in common to share tasks on our way to our own separate goals. We don’t need ideological purity with our comrades and indeed, ideological purity is part of what got us into this mess in the first place. We do need to consider whether their goals are something we can support, I’ve caught myself agreeing with things that Ann Coulter or other far right people have said but that doesn’t mean I’m going to retweet them even ironically. I have no interest in promoting an ideology or end game that causes harm even if I happen to agree with a 240 character sound bite or that a temporary alliance would help my own cause.

I like the way that Eve Tuck describes that tension between those of us moving in the same direction as the interior angles formed by two people holding hands. Those angles can become wider and more narrow as we move along the path, not only towards abolition and decolonization but guided by them because abolition and decolonization are, in the words of K Wayne Yang, lodestars as well as action. They guide our decisions and our goals, and they are themselves the actions we take. The tension in those interior angles is where relational work is being done. And that relational work is important.

Which brings me to Medicine Stories by Aurora Levins Morales. Morales is a Jewish Puerto-Rican writer and activist, raised in the rural hills of Puerto Rico and in the urban landscape of Chicago. What interests me in connection with Towards What Justice is the way that Morales asks us to create genealogies, not only of ourselves but of our communities and our movements. To think through our social justice ancestors and to understand what we have inherited from them.

Morales writes that our relationships, and beliefs about those relationships, are our true inheritance from those who came before us. This inheritance is both material, (what we have, where we live) as well as immaterial (what we believe about our material inheritance and the relationships that creates). So as we think about our social justice movements, what are the relationships that we have inherited? What are our beliefs about those relationships? Who are we born holding hands with and what do those interior angles look like?

Tiya Miles notes that in academia there are gaps in Black Studies where Native people should be, and gaps in Native Studies where Black people should be, and of course there are many people who are both Black and Native who are not seen at all. So what gaps are revealed when we do our social movement genealogies? Those gaps, those missed relationships, are also responsibility.

Now I will draw Mariame Kaba and Alexis Shotwell into the conversation, because when we examine our histories in this way we will come across things we would rather not just as when we examine our own family histories. Kaba has written that there are no perfect victims and Shotwell has written about rejecting purity and claiming our bad kin, perhaps unwanted kin may be a better way to think about them. From a social justice standpoint we want perfect victims. We want unblemished victims that we can hold up sympathetically for advocacy and we want unblemished victims in our histories.

But there are no perfect victims.

And impurities are actually relationships.

And relationships are responsibilities.

So as we move forward, guided by the lodestars of decolonization and abolition we take hold of each others hands, reaching across movements and across generations taking note of the interior angles that are formed. And in that way we build something worth having.

Ambe.