The Wendigo

Here there be monsters

The wendigo is an oft-cited parallel for capitalism and colonialism. It is an Anishinaabe monster of voracious hunger who consumes people and would eat his own lips if there was nothing else to feed on. The story goes, or rather one version of the story goes, that during a particularly hard winter a man went to see a sorcerer or a wise man or some such person for help and was given a tea to drink. The tea worked, but as with all such instant remedies it did not go well. When he entered a nearby village instead of seeing people, he saw beavers. And he ate them. All of them. People became consumables and the parallel with capitalism and colonialism is unmistakable. The wendigo is most often talked of as a cautionary tale, a warning against greed and selfishness. But it is so much more than that. Because to the Anishinaabeg, the wendigo wasn’t a metaphor or a fairy tale. It was real. And it wasn’t a monster who existed out there, it might be a member of your own community or family, it might be you.

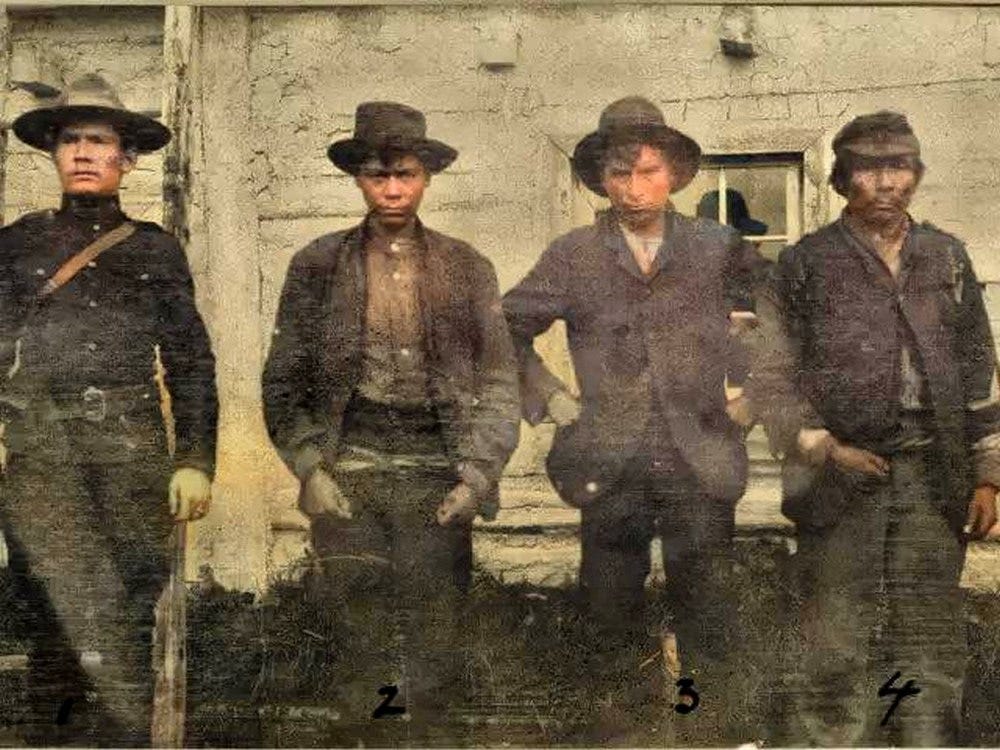

In the graphic anthology This Place: 150 Years Retold, Jen Storm tells the story of Wahsakapeequay and Jack Fiddler. Wahsakapeequay was a woman who became a wendigo. Jack Fiddler is the man who killed her and stood trial in 1907. Although Storm’s rendition is a fictionalized account, the story itself is true. Jack Fiddler, Zauwuno-geezhigo-gaubow, was the Cree headman or leader of Sandy Lake who was skilled in working with spirits and other than human beings. It was said that he could defeat the windigo, healing if possible and killing if necessary.

Sandy Lake, the community that the brothers and Wahsakapeequay belonged to, had rejected Christianity and in the early 20th century were one of the only communities in that area still living in a traditional way with little to no government involvement in their legal and religious way of life. That changed after Jack killed Wahsakapeequay. An in-law of Jack’s had told the RCMP about the killing and upon investigation the RCMP charged him and his brother Joseph, who was Wahsakapeequay’s father in law, with murder. Jack hanged himself after escaping custody and Joseph stood trial, sentenced to death. Joseph got sick and died while in custody and although an order was secured for his release (on the grounds that he wasn’t knowingly committing a crime but following the rules of his own culture) it didn’t arrive until 3 days after he died. In 1910, three years after the arrest of the Fiddler brothers, Sandy Lake First Nation signed Treaty Five and moved onto a reserve.

According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology wendigo psychosis is a culture bound syndrome occurring among Algonquin Indians living in Canada and the northeastern US characterized by delusions of being possessed by a flesh-eating monster. Symptoms include depression, violence, a compulsive desire for human flesh, and sometimes actual cannibalism. A culture bound syndrome is unique to specific ethnic or cultural populations, so only somebody who was Algonquin could be diagnosed with this disorder. As an interesting aside, there is a culture bound syndrome called “jumping Frenchmen of Maine syndrome” characterized by an extreme startle response, yelling, imitative speech and behaviour, involuntary jumping, flinging of arms, and command obedience. It has been observed in lumberjacks of French and Canadian descent living in Quebec and Maine.

Wrist is a novel written by Nathan Niigan Noodin Alder that alternates between a contemporary family who believes that they are descended from a windigo and the journal entries of a psychiatrist investigating windigo psychosis in the late 19th century. The psychiatrist accompanies the dinosaur hunter Othniel Marsh to an excavation of dinosaur bones in same area that the modern story is set and his experiences play out against a relocated history of the bone wars, a conflict between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Marsh that did take place although much further south. The threading together of these three things is interesting. The family’s creation story takes place at the same time as the dinosaur bones are being unearthed, the community worried that unearthing these bones will unearth other monsters, and indeed there are other incidents of windigo psychosis that the psychiatrist is unable to treat. The escalation of these conflicts between the Marsh and Drinker play out against the escalations that Church, the main character through whom we see the modern story, experiences as he comes of age.

Both of these books tell the story from the perspective of the monsters, their desperation to live a normal life, to be seen as human even while they are transforming, to have their choices understood, their efforts recognized. To return to the metaphor of capitalism and colonialism, this reminds us that it isn’t just the faceless corporations who are monstrous and greedy but that we are complicit in a thousand different ways and are ourselves transformed by the world we live in. We use technology that relies on slave labour, wear clothing made in unsafe textile mills. Our pensions are invested in capitalist ventures, maybe in industries that we are actively opposing even while we draw income from their profits. Perhaps we drive electric vehicles, but even so we rely on paved roads and parking lots. Our greenest energy sources can still be devastating. Solar and wind require mining. Large scale wind and solar farms have consequences for wildlife and dams flood huge areas displacing Indigenous people and wildlife and lead to increasing mercury levels in the water that in turn poison the fish. We consume food that is infused with toxins just as it is stripped of nutritional value and although we can buy organic that isn’t always possible or even better. We are workers whose labour enriches bosses even while we rely on the precarious labour of others to ring in our groceries or make our coffee.

So what do we do? Alexis Shotwell’s work on refusing purity is instructive at this point. Like the characters in Wrist, like Wahsakappequay who experienced the transformation, purity or restoration may not be possible and extricating ourselves completely (death) is an extreme choice with it’s own consequences. Church and his family drink a moss tea that controls their appetite, and we may make choices that control our consumption but it doesn’t change who we are, our overall complicity. The real change comes in recognizing that complicity is a form of connection, and that these connections shape our responsibilities. Instead of chasing individual purity we follow these threads of connection to inform our work and how we can make the world a better place rather than just removing ourselves from it. We recognize that regardless of our position, we are all workers doing the best that we can, that the only monster worth fighting is the one that began our transformations.

There are several origin stories for the wendigo, in some he is killed and remains as spirit and in others he is left alive. On the podcast I co-host, Medicine for the Resistance, we interviewed Jay Odjick, He’s a graphic novelist and comic artist and talked with us about his most well known work Kagagi which is the story of a boy who becomes a raven and kills monsters. The story was picked up by APTN, an Indigenous run television network in Canada, but only went for a single season. What Jay wanted to explore was what would happen to Kagagi after he killed all the monsters, when he was the only monster left. Then the state would view him as a monster just as the Fiddler’s in-law began to view them before he turned them in. Jay related the wendigo story the way that he had been told and that it was necessary not to kill the monster, that perhaps like Gollum in Lord of the Rings, it would eventually serve a purpose we don’t yet understand. And that perhaps in killing the monster, we would be transformed if not in ourselves then in the eyes of those around us.

The origin story of the wendigo predates colonization and Europe has it’s own monsters of avarice and mindless consumption. They were not infected by our monsters in order to become what they did. The greed of colonialism drove them to our shores and so in that way the metaphor of wendigo for colonialism becomes problematic. We did not infect them, they brought their monsters here. Their vampires and werewolves and other creatures of the night.

It feels important to recognize that while the wendigo may be a metaphor for colonialism and consumption, these were also real people, real beliefs. Anishinaabe communities experienced deprivation before and after the arrival of Europeans. It would be wrong to paint Indigenous communities as idyllic and pristine before European contact. We had violence and avarice, hunger and sexual predation. Our stories wouldn’t contain warnings against them if they didn’t exist. But what we did not have was state systems that allowed or encouraged, that provided excuses or justification. Our response, at it’s most extreme seen in the Fiddlers who themselves faced the most extreme circumstances, may have seemed superstitious and backwards to the state but was their finding of guilt and sentencing to death more civilized? Is the long slow death of prisons more civilized?

Alexis Shotwell also writes about claiming bad or unwanted kin, and to be sure nobody wanted to claim Church and his family. When Wahsakapeequay tries to go home she is rejected. But these relationships are also something we cannot simply turn our backs on. Shotwell is not writing about toxic or harmful family members, although that may be true as well, but about those relatives in our broader circle. Who claims her as a white woman. Who claims me as a Christian. What are they doing in her name, in my name, and what is our responsibility to that relationship.

It is always about relationships, what they demand of us, what they offer us. The shifting and transformative nature of the world that we live in and the things that we inherit. I could talk now about Aurora Levins Morales’ work on the relationships that we inherit and what those responsibilities call forth in us, our desire to claim lineages of oppression rather then the lineages of power and how dishonest that really is. Dishonest and impoverishing because when we sever ourselves from those relationships we sever ourselves from ourselves. Church was, after all, only part windigo. His father, questionable father that he was, had been a European Jew and survived the holocaust. But it was not possible for him to claim only one or the other inheritance. He was who he was, and both hungers were ever present.

So be careful before you write somebody off as a monster, before you judge other workers too harshly for their complicity. The windigo is not only a metaphor for mindless consumption, it is a reminder of our own complicity. And it is real, however you want to define that.