Reconciling the Wild

Thoughts from a provincial park

This summer was the summer of camping. We took cousin Eddy, our camper, out to Prince Edward Island and up to Lac Seul, a reserve four hours north of Thunder Bay Ontario. We camped in National and Provincial Parks, at breweries and farms thanks to Harvest Hosts. We boondocked at Magpie Falls. And every one of those places, the campgrounds and businesses, even the reserve, are scenes of Indigenous disposession. They are places that we have been removed from or removed to and otherwise removed. Terra Nullius and the Doctrine of Discovery decided what was wild and what was civilized and became the vehicles for our dispossession.

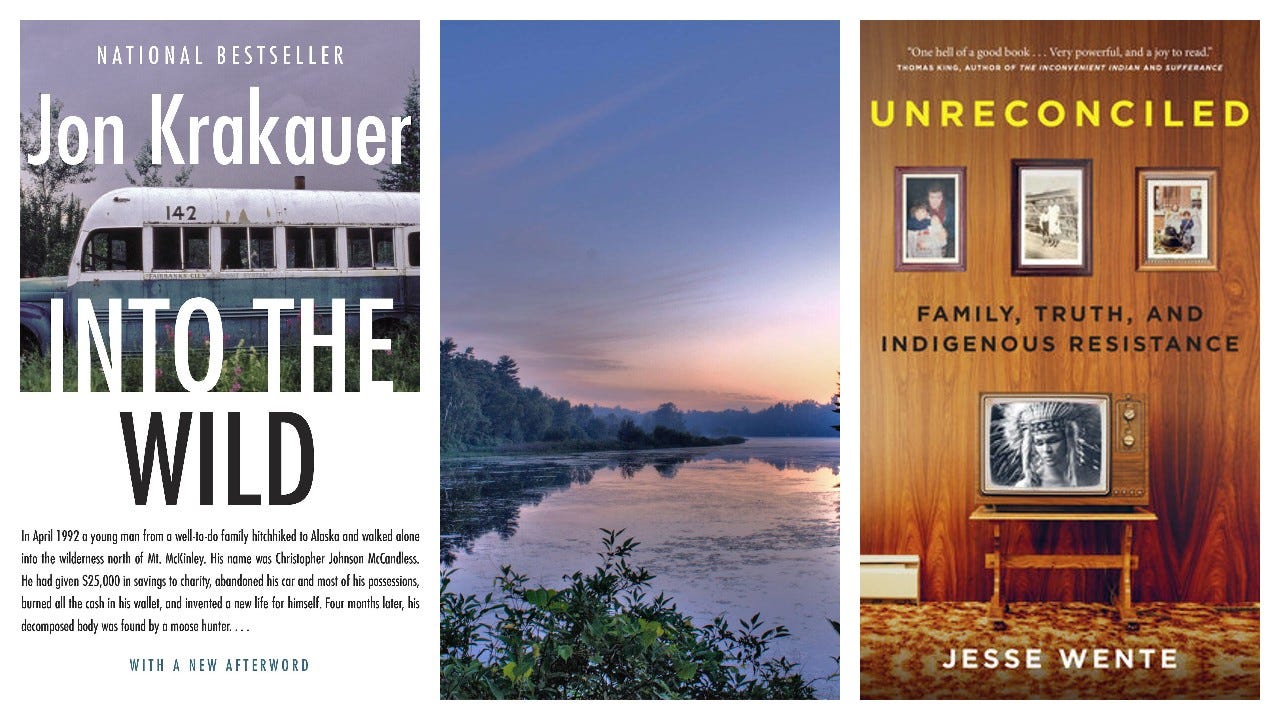

And so it was in September that I brought Unreconciled by Jesse Wente and Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer with me on our last camping trip of the year and I sat beneath the trees at The Pinery to read two books that were not as different as I thought they would be. I had no particular reason to put them together, they had arrived in my mailbox within a few days of each other and were on the table when I packed so into the camper they went.

The Pinery is about 10 minutes away from Ipperwash.

In 1995 the Kettle and Stoney Point band of Ojibwe Indians occupied the land of Ipperwash park. It was adjacent to their reserve and in WW2 it was expropriated for the war effort, a training ground I think, and then never given back. That’s the entire history of Canada but sometimes enough is enough and things get occupied. In 1975 Ojibwe warriors associated with the American Indian Movement occupied Anicinabe Park in the Kenora district. In 1990 the Mohawk put up barricades at Oka to stop a golf course development. In 2020 members of Six Nations occupied what would become known as 1492 Landback Lane in opposition to development on disputed land. Wet’suet’en. Fairy Creek. Standing Rock. Wounded Knee. Sometimes enough is enough.

But it was at Ipperwash that shots were fired. Mike Harris had just been elected Premier of Ontario and, apparently, said “get the fucking Indians out of my park” and an OPP officer shot Dudley George. There was an inquiry and in 2007 the land, over 50 hectares, was returned to the band but it would be 2016 before the settlement was finally complete. And so I read these books 10 minutes up the road from Ipperwash and that shaped the context of what I read.

There is a poem by Cheryl Savageau, so here I am writing about Indians again, and in it she describes how she gets chastised by her teacher for writing about Indians when they aren’t plainly in the text. That doesn’t mean they aren’t there, it just means the author isn’t including them. “Stop writing about what isn’t in the text” the teacher says. Savageau reflects, “which is just our entire history.”

Into the Wild isn’t a book about Indians. There’s a few individuals who are native that McCandless comes across but they aren’t the point. And yet it is a book about disposession, about a wild that doesn’t include us. It is about a young man reaching to the land for relationship, much like the squatting men do in Grapes of Wrath, and the land is silent for McCandless too. Silent and harsh, because the land doesn’t suffer fools and although McCandless did survive for many weeks despite his ill-preparedness, he eventually starved to death.

Both books are about relationship, about families that are torn apart. In Krakauer’s book it is McCandless who tears apart his family, or perhaps it is his father. We get hints of the family dysfunction, but Krakauer had agreed not to include the history of abusive behaviour until the sister published her book which is unfortunate because it is important context for why McCandless worked so hard to reject relationship, not only with his family but with everyone. He made friends and charmed people, but there was no reciprocity, no mutual responsibility, no commitment to anyone but himself. Wente’s book is about a state that disconnected us from our land, from our history, and from each other and it is a powerful description of holding on and going home.

The Anishinaabe word for great grandparent is aanikoobijigan. This is also the word for great grandchild and the root word has to do with sewing or tying and when I think about all those connections, great grandparents to great grandchildren it looks, to me, like a dreamcatcher. My threads connect me to Lula and Margareta. My children’s threads connect them to Roy and Anne. My grandchild’s threads connect them to my parents and these threads spread out and overlap and create circles of relationship.

Wente and McCandless both work to extricate themselves from colonial ideas of how to exist, but McCandless doesn’t have any other framework to hold onto and winds up alone. Wente has family and connection that he can return to and which ground him when he comes up against systems that want our stories but not us. For McCandless the land is a resource, a place to test himself and find himself but a resource. For Wente it is an ancestor, a relative. And even as he writes about finding his own place, he writes about watching his own children find theirs.

Aanikoobijigan.