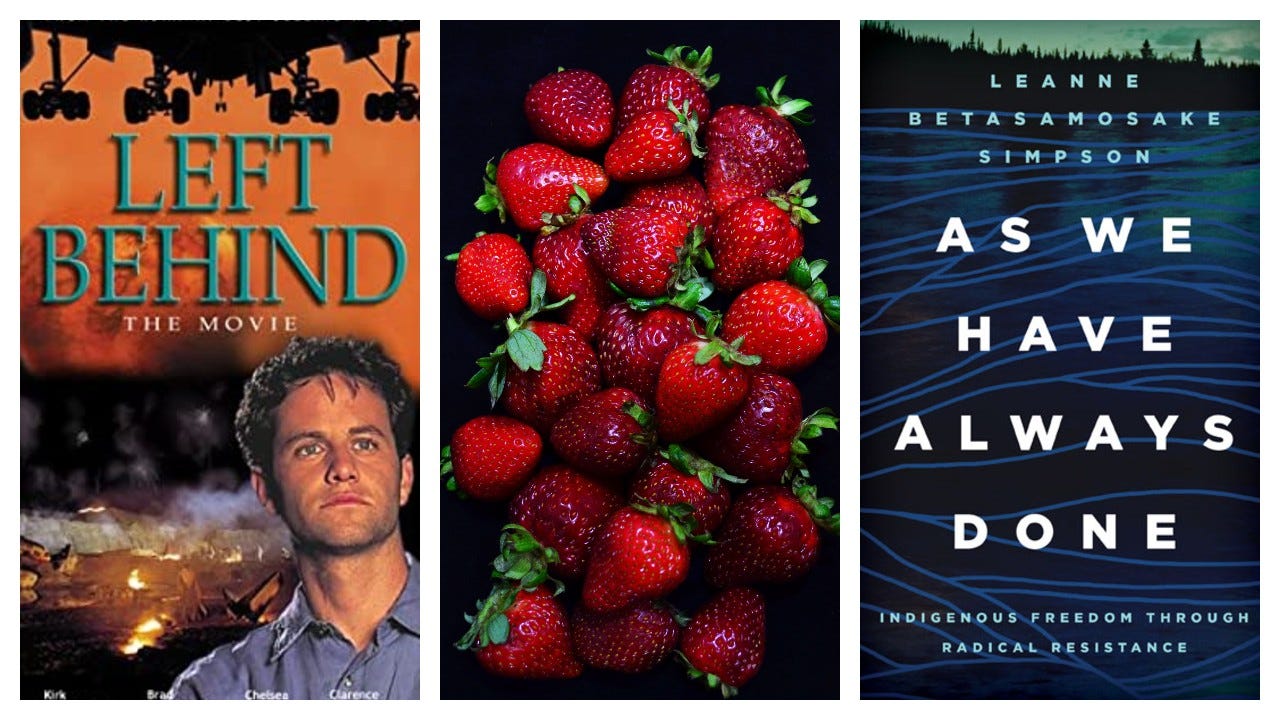

Full disclosure. I haven’t actually read the Left Behind series by evanglical author Tim LaHaye. I have seen the movies and I was raised in a church that was immersed in this rapture based end of the world theology. This series came out just as I was leaving behind what I have come to understand as a toxic and dangerous theology, but I did read a lot of other books about it before that change happened and recently, for reasons I can only describe as trauma-nostalgia, have started watching rapture themed movies starting with Thief in the Night and ending with the Left Behind that starred Nicholas Cage. There’s so many more, but only so much I can take. Mostly I just like the look on Cameron’s face in this image and so it’s a stand in for the entire genre.

For those who are unfamiliar, the premise comes from the book of Revelation which is apocalyptic literature that has recently been read strictly as prophecy that is very specific to our particular era. There will be a series of Bad Things happening and just before the final disaster True Believers will be taken away to heaven. There is a 3 1/2 year calm immediately after this during which time the Antichrist, and his sidekick The Beast, consolidate their power in a one world government. This is followed by 3 1/2 years of the worst things ever, plagues and drought, wars and famine. Then a semi-final battle between good and evil to be followed by a thousand years of Really Great Times before the final battle and then it’s all over. The good guys have won and the bad guys are defeated and cast into a lake of fire.

A lot of cultures have stories about the end of the world. Most famously perhaps the Mayan calendar ending in 2012 that spawned a number of catrastrophe movies. Even Dick Clark’s death couldn’t stop 2012 from becoming 2013 and it turned out that this end of the world predicted by the Mayans was just the end of their calendar cycle and the beginning of a new one. Worlds end and begin all the time. As Zoe Todd says in her essay Fish, Kin, and Hope, when a river becomes too polluted to support life that’s the end of the world for those fish.

The Anishinaabeg also have a series of prophecies that have become associated with the end of the world, a reading that is uncomfortably like my previous theology. There are a series of prophecies, each one prefacing the lighting of a fire. They begin when the Anishinaabeg are living on the east coast and the first prophecy is a warning about some light skinned people who are coming from across the water and so the Anishnaabeg say goodbye to their Mi’kmaq friends and head west, back to where they understood their creation to have taken place. The final fire, the seventh prophecy that leads to the lighting of the eighth and final fire is widely understood to refer to this present time.

Eddie Benton Batai, in The Mishomis Book, tells it this way:

In the time of the Seventh Fire New People will emerge. They will retrace their steps to find what was left by the trail. Their steps will take them to the Elders who they will ask to guide them on their journey. But many of the Elders will have fallen asleep. They will awaken to this new time with nothing to offer. Some of the Elders will be silent because no one will ask anything of them. The New People will have to be careful in how they approach the Elders. The task of the New People will not be easy.

If the New People will remain strong in their quest the Water Drum of the Midewiwin Lodge will again sound its voice. There will be a rebirth of the Anishinabe Nation and a rekindling of old flames. The Sacred Fire will again be lit.

It is this time that the light skinned race will be given a choice between two roads. One road will be green and lush, and very inviting. The other road will be black and charred, and walking it will cut their feet. In the prophecy, the people decide to take neither road, but instead to turn back, to remember and reclaim the wisdom of those who came before them. If they choose the right road, then the Seventh Fire will light the Eighth and final Fire, an eternal fire of peace, love brotherhood and sisterhood. If the light skinned race makes the wrong choice of the roads, then the destruction which they brought with them in coming to this country will come back at them and cause much suffering and death to all the Earth’s people.

Although Leanne Simpson Betasamosake’s book, As We Have Always Done, does not directly talk about this prophecy, I think that having her in conversation with the Left Behind series will be helpful in framing how I am coming to hear and understand this eighth fire. Because I don’t think that it is a kind of end of the world winner take all good guys win and bad guys leave forever prophecy like Left Behind. I don’t even think it is the end of the world. And I don’t think that the apocalyptic books of the Bible are about the end of the world either, perhaps in the sense that Zoe Todd is talking about but even for those fish their descendants live on elsewhere, their relatives and cousins who had moved to other rivers live on elsewhere. Life, to quote the prophet Ian Malcom, finds a way. And these literatures, these prophecies, help us to think through how we live as people in turbulent times.

The eighth fire provides us with two paths, one that is lush and green and the other that is charred and cuts our feet. The Anishinaabe have a pyro-epistemolgy, a way of looking at the world that includes fire as a tool and a weapon, a relative if you will. So these fires are not only campfires that we gather around for heat they are wildfires that consume and provoke growth. When my son burned a patch of long grass in my backyard he set off an explosion of wild strawberries who could now flourish, and they do. But he has also talked about the scorched moonscape that is left behind after a wildfire goes through a clearcut forest.

Fires come. What happens afterward is largely the result of what we have done before.

The Left Behind genre offers people a free ticket out. It’s all going to heck but you can have a get out of jail free card if you just believe. This is what I find toxic about it. There is no reckoning with what is being left behind, no need to care for the earth or the people in it, no need to wrestle with how we live beyond a very narrow scope. Did you pray the sinner’s prayer or no? And then there is the anguish that we felt over our friends who did not believe, either because we didn’t have the guts to tell them or because we did and they rejected it. One particularly painful piece of this theology is the permanence of that rejection, if somebody explained it to you and you rejected God’s gift then you were truly beyond hope. Even for the Tribulation Force, LaHaye’s resistance in the Great Tribulation, the point is to get more people saved rather than stopping the Anti-Christ because you can’t stop him because the story has already been written. There is an inevitability to the harms being committed that paralyzes any material resistance, any bending towards earthly justice. What’s the point?

By contrast, the eighth fire is about possibility for everyone. Earthly justice is the point. We live or die as a collective, not as individuals, and we live or die together. There is no us/them. There is no mention of light skinned people being sent on their way or the land being restored only for those of us who are Indigenous to this place. Yes, it can go horribly wrong but it can also go beautifully right and Leanne’s book offers us a path that is lush and green. She offers us, all of us, a way to prepare ourselves and the land for this next fire. It doesn’t have to be awful, it might be, but even that isn’t the end. It’s just the end of this particular series of prophecies just as the end of the Mayan calendar was just the end of a cycle. Even a burnt out clear cut will eventually grow back, it just takes time and care.

Leanne writes about recognition and relationship, understanding how we see each other and the relationships that we build as a result. And just as the Left Behind genre refuses the one world government and the power of the antichrist through martydom, Leanne’s book also deals with refusal but in a generative way. Colonial powers refuse Indigenous knowledge and value, and this must be met with Indigenous refusal. Refusal of the politics of recognition which only legitimizes the colonial power to recognize. Refusal of the state’s definition of issues which only entrenches their power and authority. Refusal of the way that governments deploy the politics of grief to manage our responses and deflect their accountability. Refusal of these things leads to building alternatives, building other relationships outside of the state’s authority and recognition.

Building and planting so that when the fire comes, the world will explode with strawberries.

Ambe

As always, Tuesday’s essays are free and to be shared wildly and with reckless abandon.

O!