Biskaabiiyang

returning to ourselves

It is not enough to say that this is Indigenous land. We need to act like it is Indigenous Land.

~ Naomi Klein, from an event Winnipeg April 2016.

Cited in Living in Indigenous Sovereignty by Elizabeth Carlson-Manathara and Gladys Rowe.

Land acknowledgements are becoming ubiquitous in Canada, and growing in popularity in the US. This isn’t an essay about land acknowledgements, but we begin there because people are increasingly thinking about the fact that they live on land that, one way or another, came to be in the possession of those whose roots reach across oceans. I don’t mean private property, selling or giving your land to an Indigenous person or land trust is all well and good but it doesn’t make the kind of substantive changes that we need and is a narrowing of what #LandBack means. People do this, they sell or bequeath or fundraise for land trusts and that’s important, I don’t want to diminish that. Indigenous people need spaces that are theirs, but it isn’t #LandBack. Not fully.

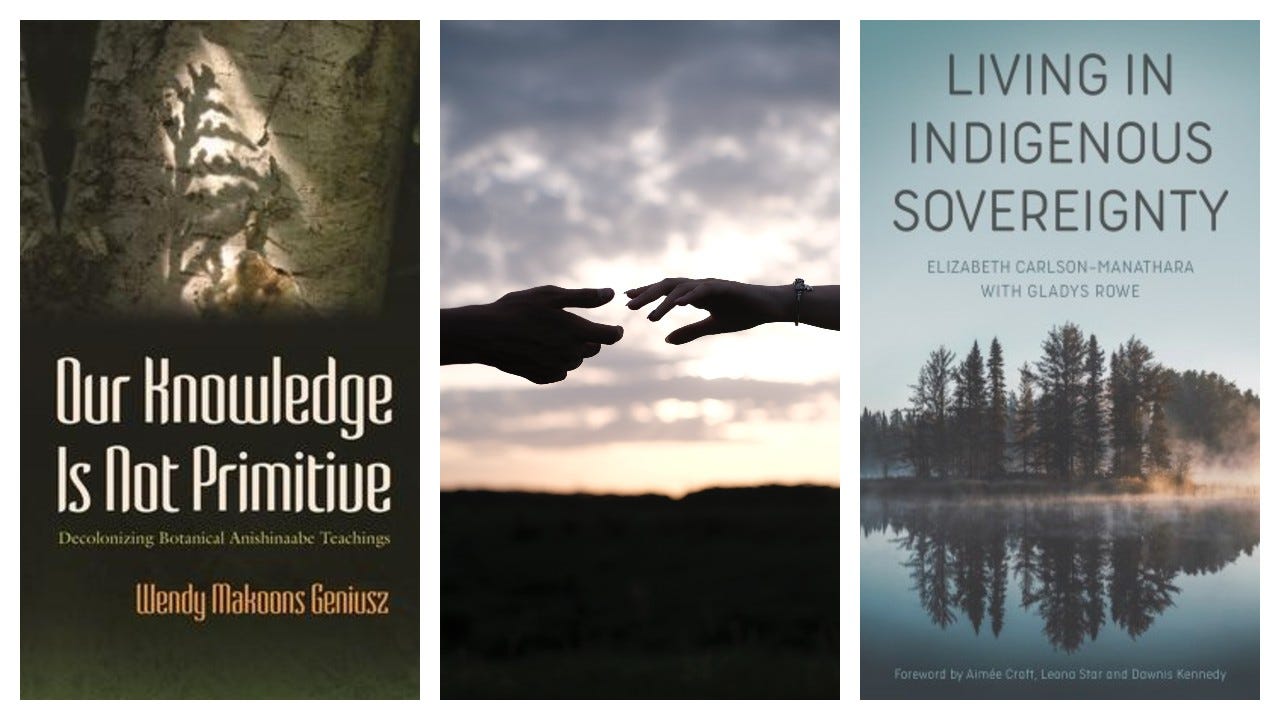

My book scatters Anishinaabemowin (Anishinaabe language) throughout the text and it was important to me to do that even though I’m not a language speaker but it wasn’t until I read Our Knowledge Is Not Primitive by Wendy Makoons Geniusz that I fully understood, or was able to articulate, why it was important to me. She also uses Anishinaabemowin throughout her text and in explaining the words she situates their concepts in the Anishinaabe world sense because that is the point. Shifting our world sense[*], unlearning the habits of colonial thought and learning to think in the ways that the people original to this place thought about this place and everything that entails. Embedding our ideas about how to live in the language and concepts that emerged in this place just as Living in Indigenous Sovereignty is about embedding our ideas about #LandBack and Indigenous Sovereignty in the land rather than on it. Changing our relationship to the land and all the beings connected with it rather than just changing ownership of it.

If the land really does belong to the Indigenous peoples, then how do we live? That’s a valid question for any of us.

These books are written to different audiences, but they connect meaningfully and these categories are never as tidy as that. Living in Indigenous Sovereignty is written for settlers and it is a collection of essays and interviews that reflect on Klein’s quote. How does a settler act like they are on Indigenous land? What does that look like on a day-to-day basis? The interviews with settlers from across Canada are reflections on how they do it, the relationships that they form which become the foundation for changed lives. Geniusz’ book is written for Anishinaabeg who are trying to decolonize their thinking, trying to find their way back to themselves. It is rooted in Biskaabiiyang.

What interested me about putting them together was a note I made while I was reading Living in Indigenous Sovereignty: the importance of unraveling your own history, knowing and undoing the myths (p.41) because that is something that both books call us to do. All of us, settler and Indigenous.

Biskaabiiyang. It means “return to ourselves” but like donating to a land trust doesn’t fully capture #LandBack, this doesn’t fully capture what the word means. For Geniusz and many others, it contains the idea of looking back and re-interpreting Anishinaabeg teachings in a contemporary context. It’s not just going backwards; it’s finding ourselves and then pulling ourselves forward into the world we live in now. So I scatter these words in my book to embed the ideas, not only of returning to ourselves but of what that means and how do we root ourselves in this place relying on the knowledge that emerged here. I do it with Anishinaabemowin because that is the language of my paternal family, that is the language of the place where I live. Part of your task is to do this in the language of the place where you live and that means building relationships with the Indigenous peoples in your area.

It is important as settlers and as Indigenous people that we return to ourselves. Settlers try to avoid this; they try to become us and that is dishonest and disrespectful to your own ancestors. I understand why you want to avoid it. Given everything that has happened I would want to avoid those relationships too but we can’t. Through my maternal family I am also connected to those who may not have intended to displace Indigenous peoples but whose presence on our lands did displace us. Through my mother I am connected to those who taught in residential schools. She did not teach in a residential school, but she did teach in a small Oji-Cree community not far from one and she held many of the same ideas about civilization that those who taught in and administrated those schools held. Sending white teachers north to teach the Indians is not the same as taking children from their families, but it still imposes colonial ideas about value and social position.

It may be that you have a distant relative who made choices about how to live in order to keep their children safe, but you are the result of those choices stretched over generations and returning to yourself does not mean reaching past those other ancestors. It means understanding why your relative made these choices on your behalf and that their community may not be your community and that is ok. It really is. Their choices did insulate you from some things just as it disconnected you from others and you can honor that relative by understanding their choices and then working with Indigenous peoples to ensure that they don’t need to make the same choices, to ensure that there are other possibilities. But we aren’t a game of Go where you set down one Indigenous relative and flip all the others from settler to Indigenous.

It may be that your ancestors suffered too. That they fled hardship and trauma as my maternal family did. But they had somewhere to flee to. Where were Indigenous people supposed to go in order to start over? There is a long history of Indian removals in Canada and the US but eventually they ran out of places to send us and so they started to eliminate us through residential schools and child welfare, after centuries of separating us from land their attention turned to separating us from each other. Returning to yourself means understanding how you were used, wittingly or not, to displace and replace and then working to ensure that we are safe from further displacement.

Now at this point I will stop to recognize the reality of the Black diaspora. First as as Indigenous people in their own right who did not come here fleeing trauma and hardship but were disconnected from their land and brought here by force. Brought here by force and then removed again and again in service to the colonial state. Removed again and again into prisons and poverty. And second as people who are Indigenous to this place through relationship. Black natives are real and carry these threads of ancestry within them. So when I talk about settlers, I am not talking about those who were brought here by force. Returning to themselves means picking up those threads and working through what it means to find home in the place you were removed to.

For Indigenous communities returning to ourselves means recognizing the place that our Black relatives have and are entitled to in our communities and not adopting white supremacist ways of thinking. It means recognizing that we have adopted white supremacist ways of thinking and rejecting those things and restoring these relationships.

It may be that your Indigenous friend has adopted you into their family, maybe you were given an Indian name and everything, welcomed to ceremonies and considered part of the community. Returning to yourself means understanding that you are a guest, cherished and beloved, but a guest who is learning how to weave your roots into this place. Returning to yourself means understanding and acknowledging your own roots, understanding that guests don’t take over the house and speak on top of their hosts.

Together these books offer a way of, in the words of Carlson-Manathara, unraveling history, of knowing and undoing the myths that we were told about ourselves and each other and the language to transform and transcend settler colonialism. There is no magic bullet. No single book you can read, no one podcast to listen to, no perfect Twitterati to follow, no percentage you can donate. Living in Indigenous Sovereignty means forming and working through relationships. Geniusz writes about the notebooks that older Ojibwe left behind about their knowledge and medicines, and the crucial information that was often left out in order to maintain control over things that could be misused in unthinking or impulsive hands. In order to make sense of Indigenous knowledge you need to have relationships.

Biskaabiiyaang

We return to ourselves.

All of us.

[*] I use world sense rather than worldview with gratitude to Tope Adefarakan, an author and academic who wrote The Souls of Yoruba folk and who has been a guest on the podcast I host with Kerry Goring. She uses world sense because world view limits our understanding to a single perspective: what we can see. And the world is so much more than that.